Mea Culpas

This is a long piece—and it’s only a tenth of the notes I had when I read the book.

I tried to include a lot of quotes but as you’ll see, Nietzsche is not the easiest to read. Oh well.

In order for you to enjoy it, some requirements: go to a couch, pretend you have a meeting, get a cup of coffee (or wine, or kombucha) and get cozy.

Click on the title of the email so you can read this on a proper website and not your (boring) email client.

Play some Bizet’s Carmen—one of Nietzsche’s favorite operas.

Take a deep breath… and let’s get to it.

Part 1: Context

Thou Shalt Not: how morality shapes society

The ultimate human question is that of meaning: What are we doing here? What is life for? Every religion, ideology, and belief system offers an answer—one that provides certainty in an very uncertain world.

But where do these beliefs come from? And what do they demand from us?

You see, every moral system asks that we buy into a series of rules about what’s good, what’s bad, what’s right, what’s wrong. These rules shape how we see the world, how we judge ourselves (and others), and even how we feel—guilt, pride, shame, righteousness. And given enough time, a moral system doesn’t just influence individuals—it steers the structure and direction of civilization itself.

Take the idea of “good”. It seems obvious, right? To be good is to be kind, generous, caring. That’s what dictionaries tell us, what we teach our children. But what if good once meant something entirely different? What if, in the past, to be “good” meant to be powerful, noble, a warrior? What if “bad” simply meant weak, poor, common?

If words as fundamental as good and bad have changed meaning, what does that say about morality itself? Is it universal? Objective? Fixed? Or is it a tug-of-war where those in power define what is “right” and “wrong”?

Nietzsche has a few thoughts on that.

The Nietzschean elephant in the room

I’m surprised On the Genealogy of Morality is only 177 pages long as this is one of the most influential texts in Nietzsche’s prolific career. There’s an additional 250 pages of notes, though. An introduction. A preface. A translators’ note. End notes, and an appendix. This is the magnitude of analysis that’s been done for Nietzsche’s short treatise, published in 1887.

Nietzsche is a misunderstood guy. He’s constantly mislabeled or oversimplified. He wrote incendiary things like “God is dead”, “slave morality”, “The Antichrist”, “übermensch”. As such, people have labeled him an antisemite, a heretic, a Nazi.

How do we make sense of it? Well, for starter I decided to read his work. Not a biography of him, not a book about his ideas, but what he typed (or probably wrote in longform) in the 19th century. And as most things in life, there is more nuance here.

Nietzsche was not an antisemite. In letters and published works, he actually rebuked the rising antisemitism of his day. It was his sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche—a vocal antisemite—who posthumously reworked and distorted some of his texts, giving them a more extreme, nationalistic spin.

He was not a Nazi. The Nazi party didn’t even exist in 19th century (Nietzsche died in 1900). He was fiercely critical of German nationalism and never advocated a race-based interpretation of "übermensch”. Hitler and other Nazi ideologues co-opted the idea and linked it to the Aryan race.

“God is Dead” ≠ “I hate God.” Nietzsche’s statement is sociological, not theological. He’s talking about how Western society no longer places its moral compass in a Judeo-Christian God. God is dead because he is no longer relevant to contemporary society.

Nietzsche, of course, had some actual racist ideas and his philosophy aligns with a Darwinian “survival of the fittest” system. But his arguments are deeper and more interesting.

In the most TL;DR manner, Nietzsche argues for a life of passions and instincts, integrity and strength. He believes our value system based on Christian values is ultimately ascetic, leading to an anti-life stance. He sees humankind as animals first, cultural beings second. He thinks society tames the beast within in order to live in harmony, at a great cost.

Master of suspicion: a framing

The French philosopher Paul Ricoeur coined the term “hermeneutics of suspicion” to describe a skeptical attitude toward surface-level understanding of texts and ideas. He mentions three “masters of suspicion” who aim to uncover hidden meanings and motives: Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, and our boy Friedrich Nietzsche.

They are suspect of generally accepted truths. Marx calls it “false consciousness”, arguing that the dominant ideology normalizes class struggle and economic exploitation. Freud talks about the “unconscious”, the hidden realm of repressed desires, fears, and memories. And Nietzsche shows the “genealogy” of concepts such as “morality”, “truth”, or “virtue” evolve over time under the influence of shifting power dynamics.

They’re all big skeptics. For them the world is not what it seems; beneath our cherished certainties lie undercurrents of manipulation, conflict and power, shaping individuals and societies.

Marx and Freud focused on structures within society—economy and psychology, but Nietzsche’s suspicion runs deeper. He forces us to question the very foundations of morality and civilization itself.

What we take for granted, our sense of right and wrong, our ideas of justice, our very understanding of progress, are not self-evident truths. They are the results of forgotten battles, where different forces fought to impose their vision of the world.

I think this is a good framing to understand Nietzsche’s radical critique of society. But this is not a treatise on all of Nietzsche’s philosophy, this is a review of a specific little book.

Part 2: What is the book about?

“What clues does the study of language, in particular etymological research, provide for the history of the development of moral concepts?”.

In my reading, the book has three central arguments.

The first is what the term “genealogy” refers to: Nietzsche’s etymological quest to find the origin of our moral terms, and to highlight their change in meaning through history.

The second one is Nietzsche’s perspective on what he considers a worse moral system. An inversion of the ancient moral system.

The third is his own philosophy. After talking about the dangers of asceticism and nihilism, he proposes a way out.

I. Language as the battleground for power

We think words have fixed meanings. They don’t. They shift over time, redefined by those in power. Nietzsche researches the original meaning of moral language—words like good, bad, right, and wrong—and shows that they use to mean something completely different.

For one, those in power always defined themselves as good.

“It was ‘the good themselves’, that is the noble, powerful, higher-ranking and high-minded who felt and ranked themselves and their doings as good, which is to say, as of first rank, in contrast to everything base, low-minded, common, and vulgar”.

Even conquerors’ prejudices live on in language. The Greek nobility, for example, didn’t just label the lower classes as bad or evil—they saw them as pitiable, as unfortunate:

“Do not fail to hear the almost benevolent nuances that, for example, the Greek nobility places in all words by which it distinguishes the lower people from itself. How they mostly define them in pity, as unhappy or pitiful or miserable, wretched, cowardly, work-slave, beast of burden… deilos, deilaios, poneros, mochtheros”.

So how does this play out in specific words? Let’s look at some of Nietzsche’s examples.

1. Bonus (good in Latin) → comes from “warrior” (duonus in Latin)

"Good" originally meant what was strong, noble, and victorious. In Greek, agathos (good) originally meant brave, powerful.

Nietzsche calls this the morality of the “knightly-aristocratic caste”.

2. Malus (bad in Latin) → comes from "black, dark" (melas in Greek, mal in Old High German)

This reflects how light-skinned Romans and Greeks associated darkness with inferiority. So "bad" became associated with the the underclass, the "other": which mostly meant the people conquered in Africa and the Middle East.

3. Schlecht (bad in German) → originally meant "simple, common" in Old German

Again, the “knightly-aristocratic caste” viewed the simple and common as inferior.

4. Villain (evil, bad person in English) → comes from "peasant, serf" (villanus in Latin)

This isn’t mentioned by Nietzsche but it highlights the same idea. I read it on the excellent A Distant Mirror, about the Black Plague in medieval Europe.

Originally, it just meant "someone who worked the land," but as feudal lords saw peasants as dirty, lowly, and untrustworthy, villanus became "villain": a symbol of wickedness.

Contemporary Examples

I decided to do a Nietzschean exercise and see which words have changed in meaning in contemporary culture.

Obviously tons of words have changed their meaning as language is ever-evolving, but I’m talking about changes in meaning that represent a change in the moral system.

Here goes.

1. "Privilege" – from legal rights to guilt

Originally, privilege (from Latin privilegium) meant a special legal right granted to an individual or class.

Over time, it has been moralized—instead of neutral legal term, it now means "undeserved advantage" implying a condition of guilt, marked by phrases like “check your privilege”.

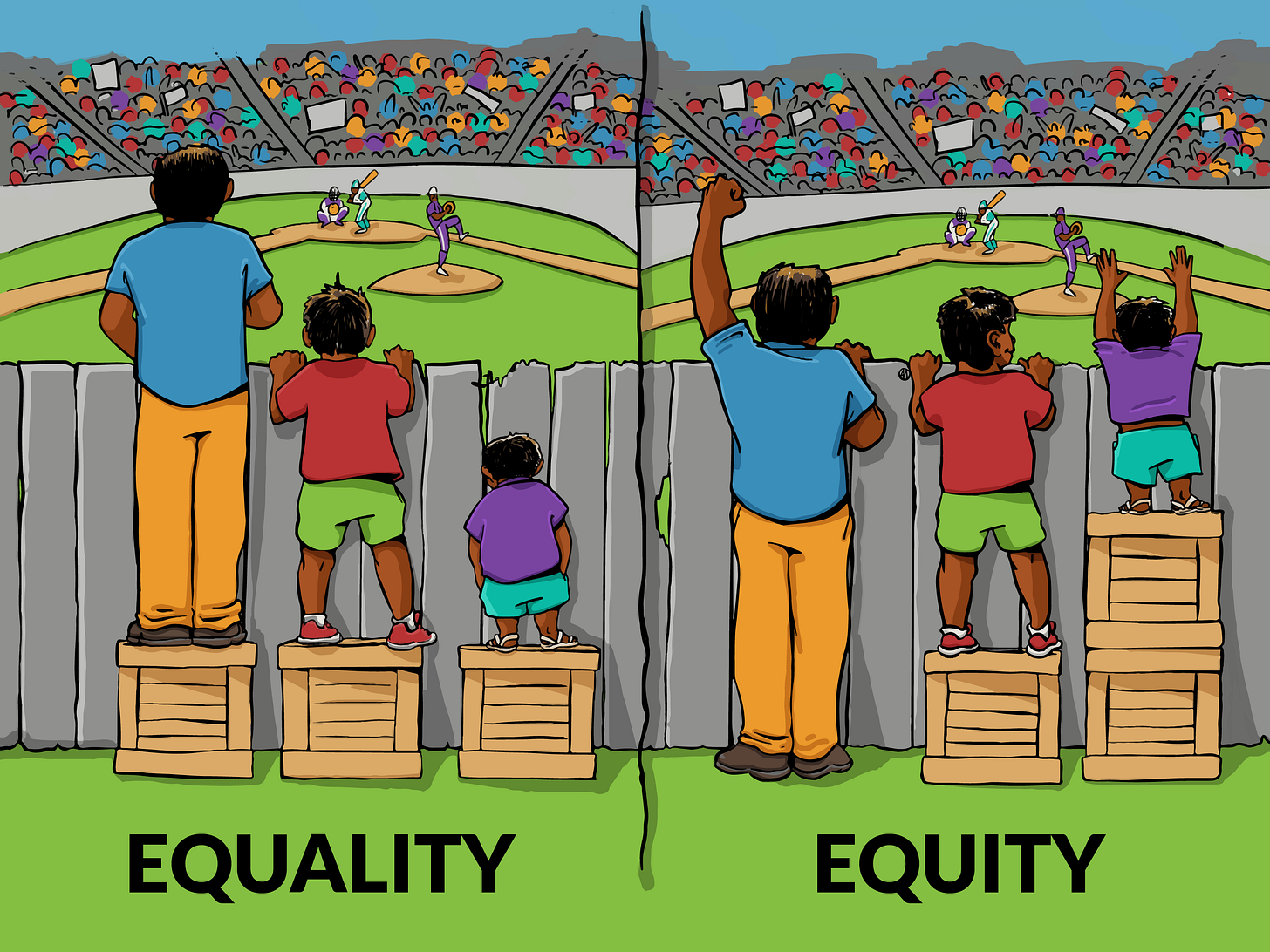

2. "Equity" – from finance to morality

The first records are in the 14th century from the Old French equite meaning "quality of being equal or fair, impartiality”. It then was used in finance and law (e.g. home equity, equity markets).

Now, it has been redefined in social justice discourse to mean equal outcomes rather than equal treatment. It’s part of a larger movement where where fairness, or justice, is reinterpreted through a lens of redistribution.

3. "Violence" – from physical harm to emotional discomfort

Violence traditionally referred to physical force causing injury.

Today, phrases like “words are violence” have expanded the definition to include emotional harm. This shift has had many legal and social implications on free speech.

You can see this at play with “microagressions”—where small statements are “violent” to someone, or even “cancel culture” in social media—where someone’s past tweets or facebook posts can get them fired or ostracized.

4. "Fascist" – From political ideology to catch-all insult

Originally, fascism referred to a specific authoritarian political movement (remember Mussolini?).

Today, it is often used as a pejorative, catch-all term for anything right-wing coded: from Trump to religion to the police.

5. “Problematic”- From intellectual inquiry to moral disapproval

This is another example of a catch-all term (brought up by my friend Emma) and it’s so true.

Before, problematic meant an intellectual problem (particularly for logic) that was unsettled. It was hard to solve.

Now it’s used as a way of showing moral disapproval without making a direct argument. Is a problematic idea factually incorrect? Offensive? Politically incorrect?

The thing with the catch-all terms is that they lose their descriptive power and become a way for people to delegitimize other viewpoints without engaging in actual debate.

Words aren’t neutral

Nietzsche’s insight remains true: moral and political struggles always leave their mark on language. Words are shaped by the victors of ideological wars.

Language is how we make sense of the world, so it’s no coincidence that changing a word’s meaning is both a moral and political act.

Before Christianity, words reflected the powerful as good and the weak as bad. But as values shifted, so did language.

Today, words have changed even further to highlight power relations. This reflects the dominance of progressive ideals rooted in postmodern views of oppression and victimhood.

Which leads me to the moral system that Nietzsche criticizes.

II. The inversion of moral values

So we’ve talked about how, originally, the powerful—the nobles, warriors, and conquerors—defined morality. Strength, excellence, and self-assertion were “good,” while weakness or lowliness was simply “bad.”

Over time, though, the tables turned. The people without power—the “priestly aristocracy” in Nietzsche’s words—driven by resentment, rose up by force of their moral system: Judeo-Christian values.

“The truly great haters in the history of the world have always been priests. It was them who in opposition to the aristocratic value equation (good = noble = powerful = beautiful = happy =beloved of God) dared its inversion, with fear-inspiring consistency, and held it fast with teeth of the most unfathomable hate (the hate of powerlessness), namely: the miserable alone are good; the poor, powerless, lowly alone are the good; the suffering, deprived, sick, ugly are also the only pious, the only blessed in God, for them alone is there blessedness, — whereas you, you noble and powerful ones, you are in all eternity the evil, the cruel, the lustful, the insatiable, the godless, yo will eternally be the wretched, accursed, and damned!”

Ressentiment and Slave Morality

Nietzsche uses the term ressentiment to describe the emotional condition—a mix of resentment and envy—of those who are not in power.

Because they can’t defeat the strong directly (by force), they reject strength, wealth, and pride as evil, redefining humility, meekness, and suffering as virtuous. This is what he calls “slave morality”: it takes what was once rejected—weakness, passivity, self-denial—and turns it into a moral ideal.

This wasn’t just a gentle swap of values. It was a subversion that changed the entire moral landscape. In noble morality, people said “yes” to themselves—valuing their achievements, courage, and vitality. Slave morality did the opposite: it said “no”.

”From the outset slave morality says “no” to an “outside”, to a “different”, to a “not-self”: and this “no” is its creative death.”

How Guilt Took Over

One of Nietzsche’s most striking claims is that this moral inversion led to the internalization of guilt. Instead of punishing criminals or enemies externally, society—via Christian ethics—made people police themselves.

Suddenly, impulses like ambition, aggression, or even healthy pride became “sinful,” fueling a relentless sense of guilt. Humans developed a “bad conscience”: the guilt they once might have directed outward (toward enemies on a battlefield) is now turned inwards.

With Christianity consolidating its power, Nietzsche argues, those who once viewed themselves as oppressed gained the upper hand in the moral domain. They enforced guilt, shame, and self-reproach as the new normal, while claiming these were the values of love, humility, and universal compassion.

The “priestly aristocracy” gained power, pretending to not want power in the first place. Power had become a bad word, so they made up reasons for their reign: “obedience to higher powers”, “justice to the people”, “fighting against ungodliness”.

In practice, though, they were as controlling—even crueler—as any conqueror, they just had a different set of tools. They moralized man’s instincts and made him feel ashamed of himself, made him feel a guilt that he could never atone for, and with that, they deified cruelty.

III. Towards a new life-affirming value system

The trap of the ascetic priest

Central to Nietzsche’s argument is the figure of the ascetic priest—the authority figure who claims to heal the suffering masses by offering moral or spiritual remedies. But Nietzsche argues there’s a power play at work: the priest becomes the gatekeeper of salvation, turning all worldly impulses into sin.

The priesthood effectively rules by redirecting ressentiment. If you suffer, someone must be to blame—be it yourself, others, or the sinful nature of the world. (Is this not how victimhood culture works today?)

“Undoubtedly, if they should succeed in shoving their own misery, all misery generally into the conscience of the happy: so that the happy would one day begin to be ashamed of their happiness and perhaps say among themselves: “it is a disgrace to be happy! there is too much misery!” … But there could not be greater and more doomful misunderstanding than when the happy, the well-formed, the powerful of body and soul begin to doubt their right to happiness. Away with this ‘inverted world’!”

Strength, ambition, self-affirmation—even happiness!—become suspect, requiring confession or penance to be deemed acceptable. This leads to asceticism as the main value.

Nietzsche’s critique of the ascetic ideal

Asceticism doesn’t simply mean giving things up. For Nietzsche, it’s the notion that life itself—our instincts, desires, and passions—is something to renounce.

And it’s not only prevalent in Christianity, many strands of Eastern thought, especially the most ascetic lines of Buddhism and Brahmanism, see worldly ties as obstacles to enlightenment. They encourage retreat from our earthly realm—be it through meditation, prayer, or rigorous self-discipline—in pursuit of a purer, higher, “nobler” state. While this is done with the aim of reducing suffering, it ends up denying life’s vibrancy and creativity.

“For an ascetic life is a self-contradiction: here is a ressentiment without equal rules, that of an unsatiated instinct and power-will that would like to become lord not over something living but rather over life itself, over its deepest, strongest, most fundamental preconditions; an attempt is made here to use energy to stop up the source of the energy; here the gaze is directed greenly and maliciously against physiological flourishing itself, in particular against its expression, beauty, joy; whereas pleasure is felt and sought in deformation, atrophy, in pain, in accident, in the ugly, in voluntary forfeit, in unselfing, self-flagellation, self-sacrifice.”

Nietzsche also includes science under the ascetic umbrella (in my view, he means scientism).

“The truthful one, in that audacious and ultimate sense presupposed by the belief in science, thus affirms another world than that of life, nature, and history; and insofar as he affirms this “other world”, what? Must he not, precisely in so doing, negate its counterpart, this world, our world?”

Scholars thought they’d abandoned religion, but science becomes its own form of ascetic worship—a quest for “pure truth”, “pure knowledge” divorced from human value and direction. This purely objective stance retreats from the richness of subjective life. (Nietzsche has a whole epistemic argument for this, called “perspectivism” that I won’t talk about because this is already too long!)

In each case, the ascetic ideal channels powerful human drives inward—sublimating aggression, lust, and ambition into guilt or cold rationalism. Nietzsche believes this fosters hypocrisy and has many unintended consequences: societies appear peaceful, but the suppressed instincts reemerge in hidden or twisted ways.

Affirming Life

This is how Nietzsche ends the book:

With this, man had meaning and he was saved. He could will something. The will itself was saved. One simply cannot conceal from oneself what all the willing that has received its direction from the ascetic ideal actually expresses: this hatred of the human, still more of the animal, still more of the material, this abhorrence of the senses, of reason itself, this fear of happiness and beauty, this longing away from all appearance, change, becoming, death, wish, longing itself—all of this means— let us dare to grasp this—a will to nothingness, an aversion to life, a rebellion against the most fundamental presuppositions of life; but it is and remains a will! …. And, to say again at the end what I said at the beginning: man would much rather will nothingness that not will…”

Such a massive insight: we’d rather will nothingness than stop willing altogether. That’s how how primal our need for purpose is—and how deeply the ascetic ideal can seduce us. And not only asceticism but any ideology, religion, value system that gives a motive or a goal.

My take is that we should say yes to everything (I literally have an post called Imagine Saying Yes). Why keep living by rules that shrink us, that tell us to repress, to kneel, to feel ashamed for wanting more? What if, instead of rejecting life, we threw ourselves into it completely?

What if, instead of guilt, we chose power—not power over others, but the power to create, to transform, to shape our own meaning? Whether we call this passion, will to power, or just plain human nature, it deserves a place in how we structure society, culture, and our personal relationships. Why not craft a way of being that embraces strength, desire, curiosity, and beauty?

If we want a deeper, more honest form of “good,” we have to embrace the full range of what being alive entails—even the parts that make us uncomfortable—and craft a moral framework that’s as rich and dynamic as life itself.

postscript 📮

Mein Gott, that was a lot, huh?

What do you think? What made sense, what didn’t?

Have you read Nietzsche? What was your experience? Which book? Which translator?

I still have more to say so expect another essay on Nietzsche next week. It’ll be fun, and very different, I promise.