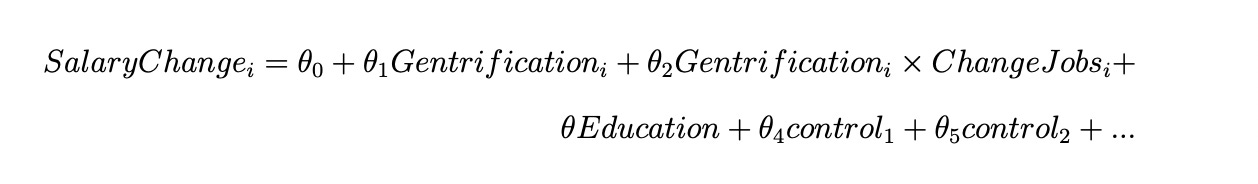

What started as a short reflection about a controversial topic turned into a rabbit hole where I wound up looking at a sociology paper with this equation:

Math still can’t provide clear-cut answers to a very human problem, though.

I offer an initial framework to describe how gentrification happens and why. I’ll try to be as nuanced as I can be on this very complex issue that polarizes pretty much everyone I know.

So, cancel your meetings, get some whisky to calm your nerves, and let's get to it.

What is gentrification, anyway?

Gentrification is a loaded word these days. People's gut reaction is to say it's terrible, that it should be stopped, that it's destroying entire cities. It is a catch-all term for everything that is wrong with capitalism and globalization.

Gentrification in its original definition means the influx of middle-class people into a working-class neighborhood, improving the built environment thereby pushing the prices up, displacing working-class people, and replacing the social character of the neighborhood. The term was coined in 1962 by Ruth Glass, a British sociologist, to explain what was happening to London's working class neighborhoods.

While this is the first coinage of the term, gentrification has been going on for centuries. The wealthy move around by choice. The poor move around by necessity or force. Other euphemisms for similar phenomena throughout the ages have been urban renewal, modernization, rehabilitation, migration, clearance…

Even Islington— the working class neighborhood Glass writes about— had been part of a larger pattern of resettling. Working class people moved there because of a previous (forced) displacement.

The borough in the late 18th century was were well-to-do businessmen and artisans lived. It wasn't until the mid 19th century that the “social character” of Islington first changed. Clearances to build new industry in inner London forced low-income workers to move to Islington and other northern boroughs. When the influx grew, middle-class people left as the area was deemed "unfashionable" and Islington fell into a long decline. Almost a hundred year laters, in the 1950s, middle class people came and gentrified the area (again).

To be honest, to look at the history of cities is to look at a history of displacement. People are forced to move in the name of politics, war, agriculture, industry, commerce, infrastructure, etc.

Now, I'm not saying that gentrification is good, or that its effects are only beneficial. I'm saying that it is unavoidable. Cities are in constant flux. They grow, stagnate, and sometimes decline. People will continue to move in and out of districts in a dynamic process that involves economic, social, and even ecological forces.

Stages of gentrification

I think of the stages of gentrification like the s-curve used by Carlota Perez to describe technological revolutions. As a new technology appears, it goes through distinct periods of growth and maturity. (It’s a pretty interesting read and I really recommend her book.)

The s-curve is similar when a district starts getting gentrified. In the early stage, the price and popularity rise slowly. In the transitional stage, as more people move in, more businesses and restaurants open up, the growth rate shoots off. (You can call it growth, or price or development, they’re all related). This is a time where the district changes dramatically. Infrastructure improves, prices rise dramatically, and the social character of the area changes. In the late stage, real estate development matures, prices stabilize (remaining expensive), and the district becomes a bit blander. The displaced people move somewhere else and start gentrifying another area and the cycle begins again.

Yes, this is obviously a simplification and not every district or neighborhood gets gentrified the same way, yadda yadda yadda.

Early, or Urban Uncovering

(artists, students, LGBT community, immigrants)

Local neighborhoods that are a run down but still hold interesting architecture, or are in a good location get noticed by pioneer gentrifiers. These are people who are new to the city or who might’ve been displaced from another more expensive area.

They see the potential and move in, paying cheaper rent in old or neglected buildings buildings. With time, they restore some buildings, open up new businesses, and create cultural cachet for the neighborhood (i.e. art galleries, graffiti art, etc.)

Transitional, or Urban Revival

(experienced tourists, service workers/professional class, small-scale developers)

Then comes the transitional period. Word of mouth increases and more people come to hang out. There is further demand for new or restored housing so small-scale developers take notice. Expats move to this area. The area gets noticed by the district or county and they start making improvements to urban infrastructure. Hip restaurants and bars open up, along new businesses catering for a wealthier class.

This is a sweet spot. Not only is the area improved with infrastructure, many of its original residents are benefiting from improved transport and greater opportunities via a stronger local economy.

However, the trend doesn’t stop here.

Late, or Urban Saturation

(large-scale developers, global capital, big brands, mainstream tourists, wealthy people)

As more tourists visit and even wealthier people move in, the area transforms massively. Most small businesses and local brands cannot afford to stay so international brands take over. Successful restaurants stay but experimental ones, along with noisy clubs and bars, leave. Large companies might choose to set up offices here. Urban infrastructure continues to improve; some type of “beautification” project might happen (i.e. removing graffiti, removing street food, etc.). The district becomes homogeneous. Interestingness takes a toll.

The district becomes “wealthy”.

The big issue

The most palpable issue that comes with gentrification is the increase in prices. As a neighborhood gets fashionable on a global scale, demand for rents grows exponentially.

This has all sort of ramifications on the local real estate supply. For example, rents have skyrocketed in the Roma and Condesa neighborhoods in CDMX, led by the demand from Americans and “digital nomads” who work remotely. Airbnb poses another problem as more landlords put their apartments on the platform to earn more money vs. a traditional long-term rent contract.

With this increase in prices there is a risk of losing what makes the neighborhoods so special: the idiosyncratic local culture.

This is where most people end their discussions and nod at how terrible it all is and how we should stop it. But let’s talk.

The opportunity

Continued international attention to a city or district creates a lot of wealth. More high-expenditure tourism benefits the hospitality industry, but also small businesses too: artists and craftspeople, musicians, tour guides, shop owners, etc.

The main focus should be in how to provide opportunities to all of the district’s residents to participate in the prosperity boom. As Jane Jacobs, in “The Death and Life of Great American Cities”, argues:

“When people say bring back the middle class to cities, what they should be thinking is how to create a middle class of the people who are already in the city.”

What we need is true urban revival. Not only improving upon the local environment, but strengthening the local economy and the local culture.

Diversity is key for this. The curse of successful neighborhoods is that they become so expensive that most residents and small businesses are forced to leave and the very interestingness and heterogeneity that made them popular gets lots. They become bland, boring and homogeneous.

Neighborhoods should offer enough diversity and opportunity that people might be able to change jobs, change interests, have a family, earn more or less money, and still be able to remain in their same neighborhood.

One promising example of a new re-mixing of cultures is the culinary industry in Mexico City’s most popular neighborhoods. I see (and have met) chefs from the USA, from Singapore, from Italy, from Thailand coming to CDMX, falling in love, and opening up a restaurant that showcases their cuisine authentically (an added benefit especially for more niche cuisines), or they opt to mix their cuisine with Mexican ingredients or techniques. It's a positive sum thing. These amazing restaurant could not have existed anywhere else.

The interestingness of the neighborhood should be enhanced not diminished with the influx of new people. International talent mixed with hungry local talent can create amazing stuff.

I know I’ve barely scratched the surface on this topic, but we’ll talk about it in later essays. You can leave a comment and fight me on how wrong my take is.

Interesting Reads:

Roma Norte's Program for Urban Development (in Spanish)

Six Phases of Gentrification in Vienna

Displacement and the Consequences of Gentrification

It'd be interesting if there were a way for appreciating property values to benefit the median person, too. Seems unrealistic to just try to help everyone to buy rather than rent though.